|

by Glenn C. Koenig, webmaster at Town Wide Mall

The two terms in the title of the article may need some explanation: Overlay District: I published a story on this web site, back in November 2023 on the “Powder Mill Road Corridor Initiative” which explains what an “Overlay District” is. Here is the link: https://www.townwidemall.com/news/plans-in-progress Near the end of that story, I included a section called “Some Definitions and Comment” to provide a brief understanding of Zoning Laws, and what an Overlay Zone or Overlay District is.

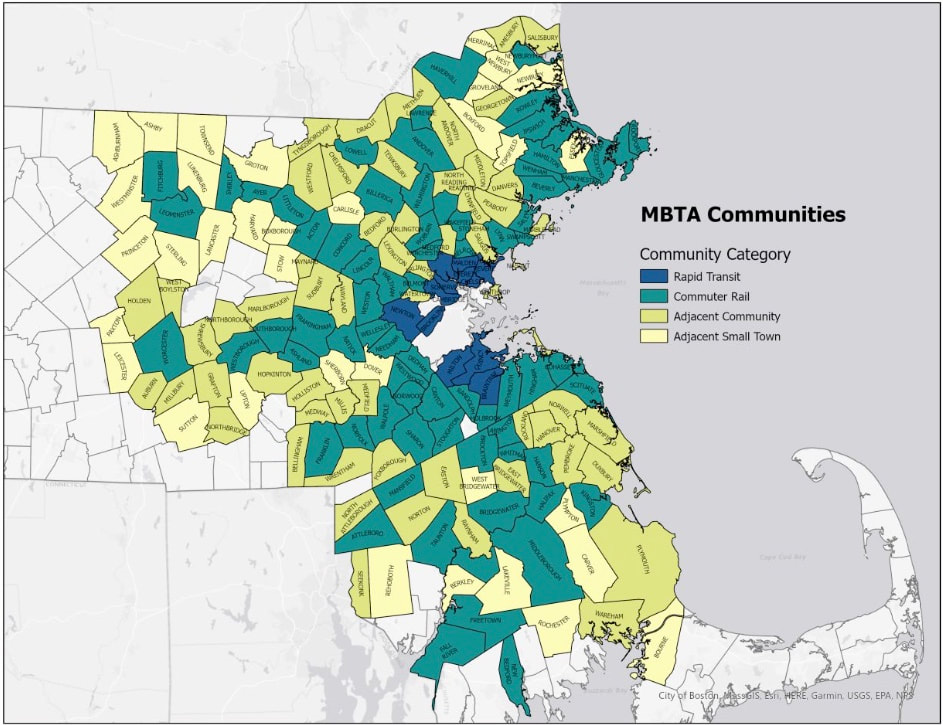

(Note: To see other stories published previously, choose "News Index" from the menu above.) MBTA Communities: It may seem odd that Maynard voters are being asked to vote on a zoning law regarding the MBTA. After all, Maynard does not have any MBTA service within its borders. However, Maynard is included under this law because we are defined as an “MBTA served community.” That means, although the T doesn't pass directly through our town, we abut (share a border with) the Town of Acton, which is served by South Acton Station, less than a mile away.

As to "Why" the law was passed, the state makes its case on its web page devoted to the reasoning: https://www.mass.gov/info-details/multi-family-zoning-requirement-for-mbta-communities To summarize, we here in Massachusetts are facing at least two serious issues: Very expensive housing, due in part to a shortage of available housing units, and a seriously inadequate transportation system, due partly to our history of development dating back to before the United States was founded! (see the "Background" section, below, for more details.) For "How," the law was developed, it was included in a section of a 101 page bill passed by the legislature in 2020 and signed into law by then Governor Charlie Baker in early 2021. One description of the process (sausage being made, so to speak) is described in this news report from WGBH: https://www.wgbh.org/news/politics/2024-02-22/a-surprising-history-of-how-a-bill-became-the-mbta-communities-law For "What," ... the quick answer is that each town listed must have at least one zone which permits multi-family housing, as specified by details in the law, "by right." That means a developer may build multi-family housing within such a zone without a special hearing to get permission by local town government. The state web site has a question and answer page devoted to the details on how this all is supposed to work: https://www.mass.gov/info-details/mbta-communities-law-qa However, although the language on that web page seems quite clear, it doesn't mention much of anything about the controversy surrounding it. In a sense, what it gives is the "state's opinion," but back in mid February, voters in the Town of Milton rejected a zoning plan that was originally designed to comply with the law. The story about what happened in Milton was covered by WGBH news as well as many other news organizations. (Note: the photo at the top of this story on their web page is the same as the photo at the top of the story referenced above, under "How," so please don't think this is the wrong link). https://www.wgbh.org/news/local/2024-02-15/milton-voters-reject-new-housing-plan-violating-the-mbta-communities-act Since the vote in Milton, there have been a series of follow up news stories on the controversy. For instance, the state Attorney General subsequently sued the town of Milton in court, the state cut off certain state financial aid to Milton, and attorneys representing Milton subsequently responded by filing motions in court to contest the suit. By now, the state's supreme court is scheduled to hear arguments on the case this fall, as reported by WBUR back in March: https://www.wbur.org/news/2024/03/19/massachusetts-housing-lawsuit-andrea-campbell

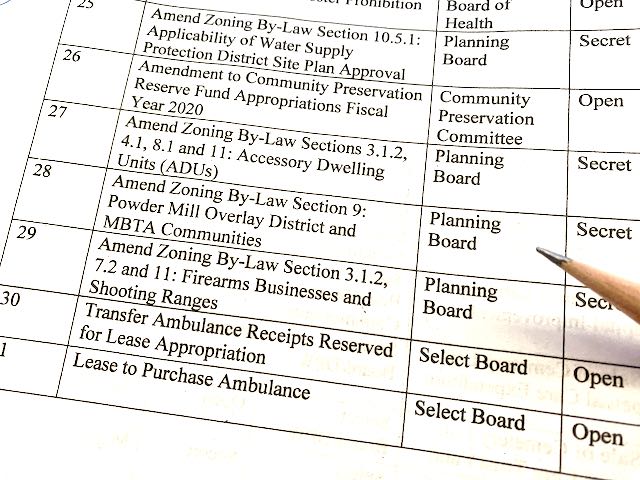

Article 28 has two parts. The first part establishes a new type of zone, the Overlay District, by adding a new section, 9.7, to our zoning by-law. The second part, starting on the bottom of page 38 in the warrant, designates the parcel of land at 111 Powder Mill Road to be included in this new zone. Commentary The issue of housing has been controversial in Massachusetts for decades. Residents of existing towns are understandably concerned about possible changes and impact to the character of their towns. They are often concerned about overall density (and the impact on town infrastructure, such as water, sewer, roads, schools, and other town services), as well as having to accommodate new buildings that may seem out of place. Some people are of the opinion that housing that's "affordable" will end up with people who don't fit into their idea of good neighbors. On the other hand, the shortage of housing is already having an impact on all of us, but it's largely invisible, when compared to something like the appearance of a new building. That is, the lack of housing drives up the cost of living, for both house purchasers and renters. People who might live and work in our state may defer because they conclude that they won't be able to make ends meet. People who already live here may reach their "breaking point" financially, and decide to leave Massachusetts to live elsewhere where the economics are more favorable. Even though more jobs can now be performed online, many service industry and other jobs require traveling to the workplace in person. Couple this with sad state of our transportation infrastructure (see notes in the "Background" section, below), and the problem gets worse. Anyone wishing to move to lower-cost housing, at a greater distance from their place of work, faces an arduous commute, whether by car or public transit. The law requires Maynard to add 474 units of housing, 10% of what we already have (4,741 as of 2020) on a land area of at least 21 acres. Since we don't have any MBTA stations in town, the location of this new housing can be anywhere in town. We are fortunate to have a parcel of land well suited to comply with these requirements, without having to directly impact our existing neighborhoods or downtown area. If the existing building can be converted to residential use (apartments or condominiums), we are likely to have less disruption from construction traffic than we otherwise might if a new building had to be built from scratch. However, it's very important to note that vote proposed in Article 28 only changes our zoning by-law; it does not specify when or how these additional units will be constructed or occupied. Since it may be some time before anything is actually built, Maynard has time to assess the impact of additional families and individuals on our existing infrastructure, including water, wastewater treatment, energy sources, and transportation. The intention of the law is to place people as close to public transit as possible, in hopes that we can reduce the amount of automobile traffic on our roads and highways. When I asked Bill if water was our most limiting factor, he expressed the opinion that transportation may also be significant. Therefore, it may make sense for us to consider some kind of local shuttle bus or other method for the future, perhaps supported by state funding, to help people get around without having to add more cars to our roads and the surrounding highways. Such a conveyance could make stops at the South Action Station, as well as downtown Maynard, area food stores, and various residential locations. I want to note that the Overlay District is not just for compliance with this law. By passing this by-law, we stand to improve Maynard in a number of other ways in the future, including not just for our own transportation, shopping, and recreation, but also to provide better support for wildlife along the Assabet River, among other things. In light of all this, I recommend approving Article 28. Unfortunately, I will be on a trip out of town so I will not be able attend the meeting myself in order to speak on the article or cast my vote. Background Housing: Because development in Eastern Massachusetts extends back over 300 years ago, we are now stuck with the results of decisions made long ago when no one could conceive of today's housing technology or requirements. Part of this legacy is the dominance of single family housing zones in many of the communities surrounding Boston. The legacy of single family housing originates in our largely agricultural economy, prior to the industrial revolution in the 1700s. There seemed to be plenty of land, so people spread out and set up farms and housekeeping as they saw fit. Now we have gone through the manufacturing era, which has since ebbed away as global trade has provided us with goods manufactured elsewhere in the world. This change has caused most old factories in Massachusetts to close or be redeveloped for new uses during the last century. Maynard's own mill complex is just one example. Unfortunately, we're stuck with many of the decisions made long ago as to the placement of individual properties, roads and highways, and rail lines. That brings us to transportation.

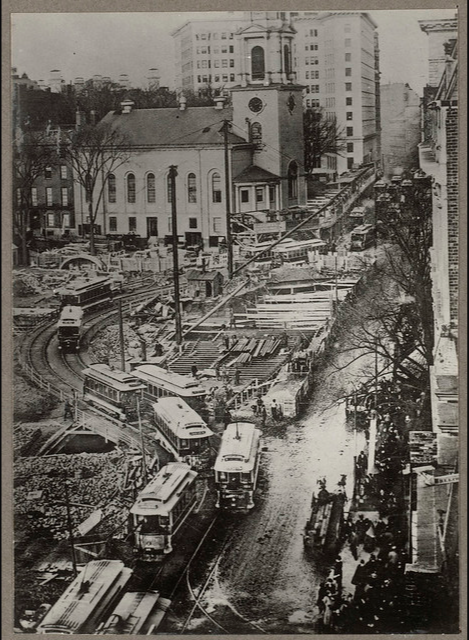

For example: Our four rapid transit lines each have their own technology: transit cars from one line cannot be run on any of the other lines. The green line is the descendant of that first subway, which is why it runs with overhead lines to power it, (as trolley cars have done, since electrification) instead of a third rail. The green line also has such sharp curves that its cars must be "articulated" (have a flexible joint in the middle) just to get around the sharp curves built for smaller trolley cars, especially at Boylston Station at the corner of the Boston Common. Our rapid transit lines and commuter rail lines were all designed primarily with commuters in mind. That is, many people who live in the outskirts of Boston (in the suburbs that were built after World War I and World War II) commute to work in the inner city. This "spoke and hub" arrangement is great for that need, but as manufacturing, warehouses, and offices moved out of the inner city, the need to travel from one suburb to another is poorly served by the system. For example, if you live in Maynard but have a job in Framingham, you'll likely use a car to drive there. The idea that you would ride the T all the way into Boston, then back out to Framingham is absurd for any but the most extremely patient traveler. Consider also the fact that North Station and South Station serve completely separate commuter rail networks, without any rail connection between them. This is a burden for anyone who wants to travel up the east coast from the south and continue on to New Hampshire or Maine, or anyone locally who lives south of Boston but must work north of the city. After all, you can't just "change trains" in Boston, you actually have to take a taxi or Uber or two different subway routes, the red and the green or orange lines, to get there, each with its own wait time for the next train. Private Transportation: Our pattern of roads (for travel by truck, automobile, or bicycle) are famously derived from cow paths centuries ago. Attempts to remedy this by building new highways in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s ended up with resistance from people who did not want their densely settled or historic neighborhoods to be demolished and their communities sliced into pieces by major thoroughfares. At one time, Route 3 was planned to run right down through Lexington and Arlington to join Route 2 in Arlington Heights (where Route 2 widens to 4 lanes). Those towns fought the plan and won, so Route 3, as a divided highway, ends at Rt. 128, with ramps to join Rt. 128, near the Burlington Mall. The infamous "inner belt" (I-695) was planned as an expressway to form a tight circle through Boston's closest neighboring cities and towns to connect with I-93 and then go around through Somerville, Cambridge, Brookline and towns south of there. This plan, if ever implemented, would have wiped out numerous neighborhoods that had existed there for hundreds of years. There is a retrospect on this web page from Bloomberg News: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-05-01/boston-s-highway-that-went-nowhere-lessons-from-the-inner-belt-fight-40-years-later

Route I-95 was originally planned to run from Rhode Island directly into the heart of downtown Boston and then continue directly up through Chelsea and Saugus (along the current Route 1), then further up into New Hampshire and Maine. However, plans to build it along that route were abandoned in the early 1970s after resistance from the numerous neighborhoods that would have been destroyed. Now, only the Orange Line, Amtrak, and commuter rail lines run in the corridor south of the city. These take up a much narrower strip of land when compared to a multi-lane limited access highway. After years of delay, the government finally decided to designate much of Route 128 as also Route 95, routing it around the city instead. These are just a few examples of the transportation challenges in the greater Boston area that have been recognized for a long time by now, but have remained unsolved due to a whole host of problems for which no suitable solution was found.

3 Comments

5/16/2024 07:59:56 am

I agree with Glenn Koenig's comments and intend to attend next Monday's Town Meeting. The one thing I would add is that Maynard ought to consider trying to esablish local shuttle service available to all not just to the South Acton train station but also to West Concord, Concord and Emerson Hospital.

Reply

Dinesh

5/16/2024 07:29:41 pm

I wish they allowed non seniors to use the shuttle as well with perhaps higher rates but lower than typical car rentals. i definitely agree that seniors need it most but more usage by attracting everyone would give more revenue and perhaps attract more funds from state/federal due to more usage.

Reply

O'Leary, Jr. Joseph J.

5/16/2024 01:07:29 pm

You are providing a great public service. I appreciate it very much.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed